Fernando Valenzuela had a screwball, however he definitely wasn’t one.

Take it from Mike Scioscia, the Dodger who caught most of his pitching begins for greater than a decade, beginning with the superb run of 1981 that created a time period that can dwell perpetually on the planet of sports activities: Fernandomania.

Again then, and even now, the belief is that any 20-year-old rookie coming into the main leagues, particularly one who didn’t communicate English, can be quiet, a bit intimidated, typically a nervous wreck. Scioscia debunks all that. He says that, in most conditions on the mound, Fernando knew precisely the way to deal with issues, what to throw and the way to throw it. As quickly as he acquired to the massive leagues, he was a monster, Scioscia says.

“You could see his leadership in the clubhouse,” the veteran catcher and former Angels supervisor recollects. “He seemed to keep everybody calm. He just knew he was good. He knew what he could do and he let his pitches do the talking.”

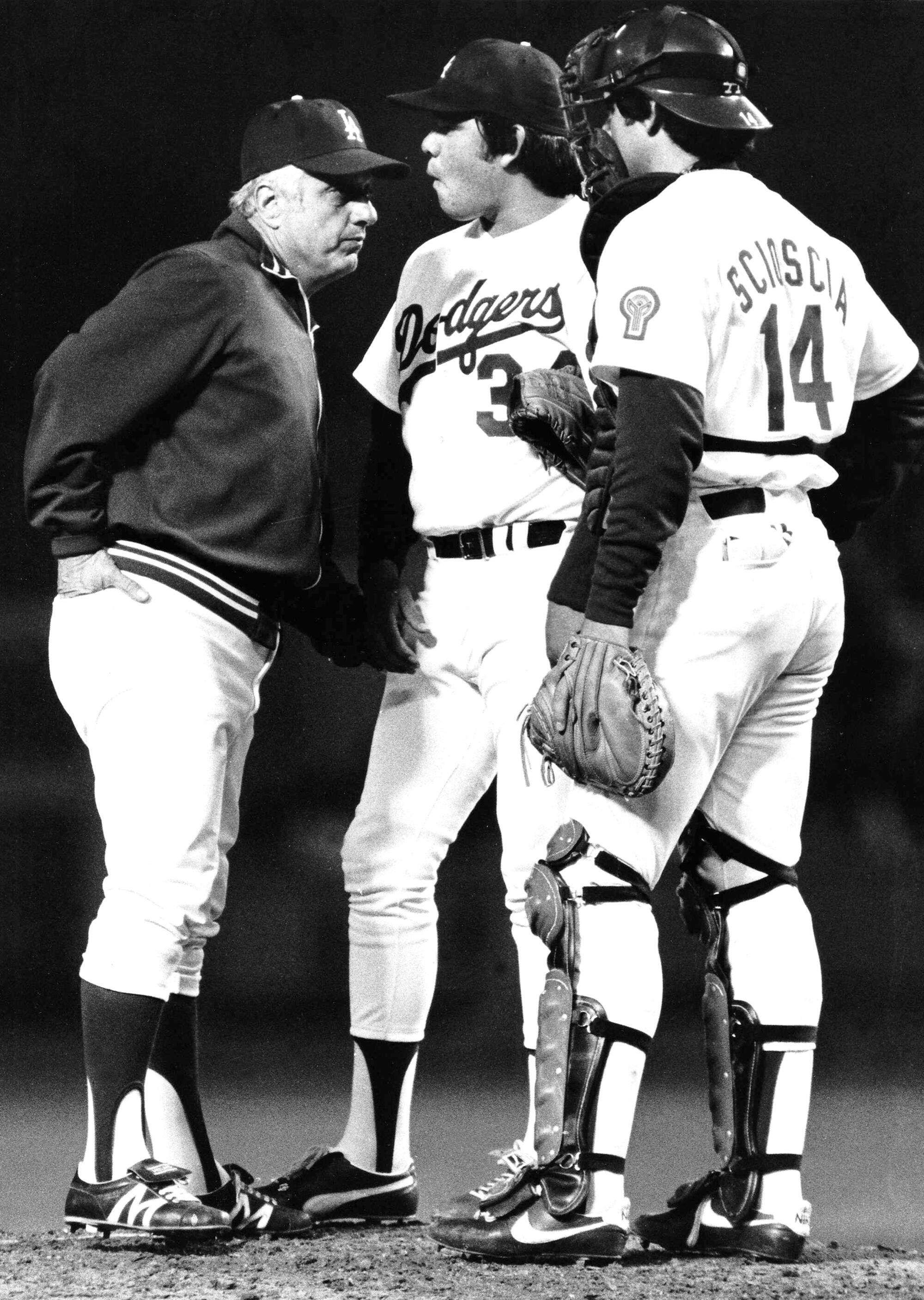

Dodgers supervisor Tommy Lasorda talks with beginning pitcher Fernando Valenzuela (34) and catcher Mike Scioscia (14) in 1981.

(Jayne Kamin-Oncea/Los Angeles Instances)

Scioscia is like so many who’re nonetheless reeling from Valenzuela’s current dying: So younger at 63, so intertwined with Dodger lore, so distinct in character. Scioscia couldn’t name it a loss, as a result of the phrase didn’t fairly cowl it.

“When I heard he had left the broadcast booth [Sept. 24,]” Scioscia says, “I knew it was serious. I called and asked to see him, but he wasn’t seeing anybody.”

Visits would have been good, however there was no use for additional legacy-building. Fernando Valenzuela was a power to be cherished, admired and remembered fondly. He was the 20-year-old child from the dusty fields of Etchohuaquila, Mexico, who was summoned to be the beginning pitcher within the ’81 season opener when two different starters with expertise and seniority got here down with accidents.

“He had thrown an entire bullpen [simulated game] the day before,” Scioscia says, “and Tommy Lasorda asked him if he thought he could go. He said, ‘Hell, yes.’ ”

Fernandomania was born.

He beat the Houston Astros, the group that had knocked the Dodgers out of the playoffs the yr earlier than, and by no means stopped till he had gained eight in a row, 5 of them shutouts. Baseball didn’t know what to suppose. Los Angeles went gaga. Quickly, The Instances was going up two pages in its sports activities part each time he pitched. With the Dodgers right down to the hated Yankees, 2-0, within the World Sequence, Fernando took the mound for Sport 3 in Dodger Stadium and stayed there for 147 pitches. He gained, 5-4 — the successful run scoring when Scioscia, pinch hitting, grounded right into a double play with a person on third and no person out.

“I’m not sure who was catching him made much of a difference,” Scioscia says. “He could throw to a brick wall. I’m not sure, either, if my little bit of Spanish made any difference. I got it playing winter ball in the Dominican, and worked hard to keep it.”

Scioscia says he might talk with Fernando properly sufficient to exit to the mound now and again and focus on pitches.

“I went out one time and told him, in Spanish, to throw his next pitch, his famous screwball, into the dirt,” Scioscia says. “The batter had two strikes on him, there was a runner on second and two out, and I figured the batter would swing no matter what. Fernando said, ‘OK, but you block it.’

“I said I would, Fernando threw the perfect dirt screwball, the guy swung and missed and the ball skipped past me. Now, we have men on first and third and I feel terrible. Next batter gets two strikes on him, I ask for the same screwball in the dirt. Fernando looks at me, then throws it. The guy swings and misses. This time I block it.

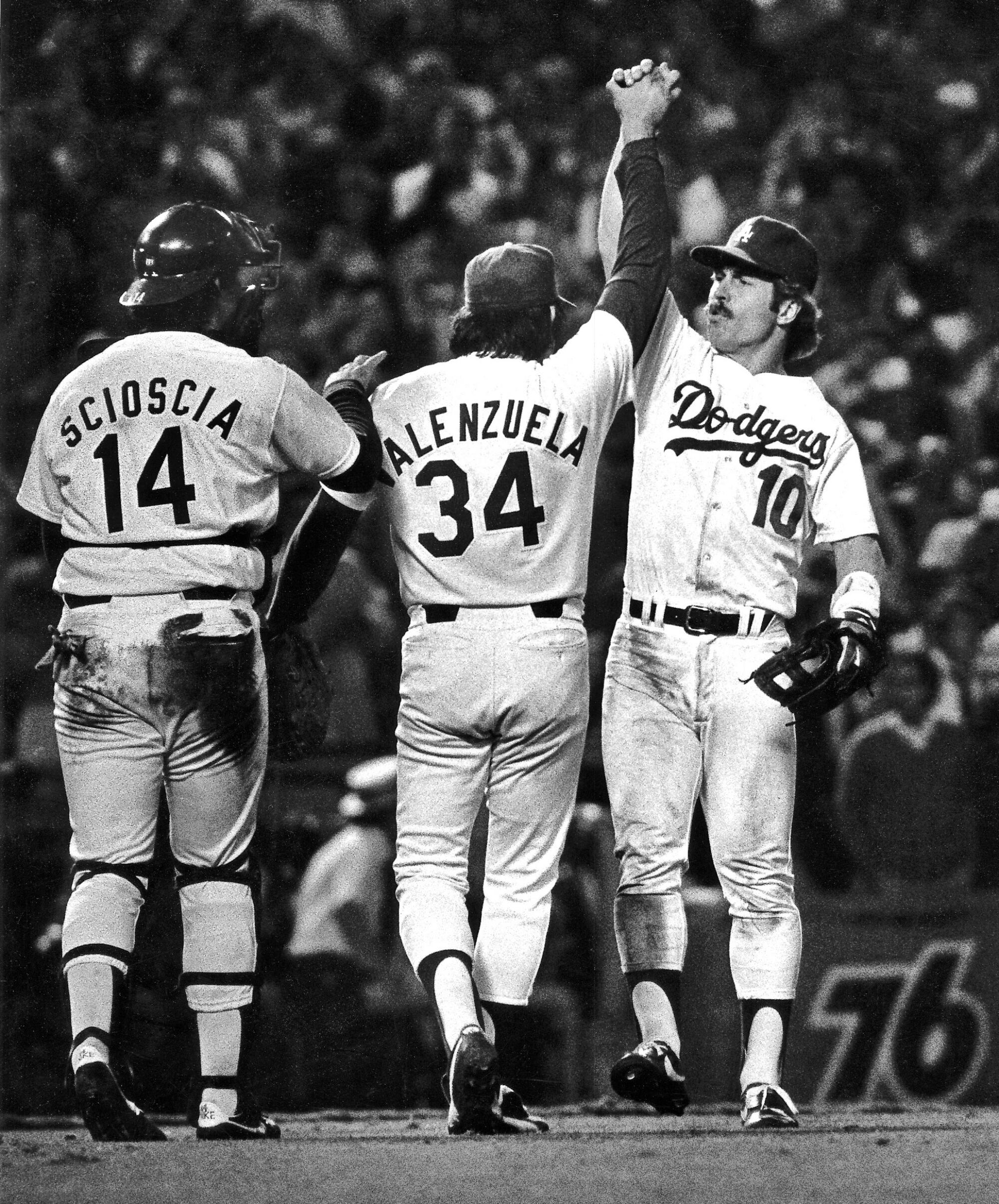

Dodgers pitcher Fernando Valenzuela (34) is congratulated by teammates Mike Scioscia (14) and Ron Cey (10) after pitching a complete game and beating the New York Yankees 5-4 in the third game of the 1981 World Series at Dodger Stadium.

(Robert Lachman)

“We go to the dugout and I feel rotten. Fernando is over on the bench, toweling off. I don’t want to look at him, but I do. He smiles and says, in perfect English, ‘It’s OK, Mikey. I still love you.’

“I had one game,” Scioscia continues, “where I got sawed off twice (hit the ball on the thin part of the bat). I had wood splintering all over the infield. The next day, Fernando is out before the game, playing fungo and trying to hit everything close to his hands, teasing me. ‘Look, Mikey. Look where I hit the ball.’ ’’ This was the same Fernando Valenzuela who occasionally brought out a cowboy lasso and snared teammates as they walked through the clubhouse.

That sense of fun carried over to the night of June 29, 1990, when the Cardinals were in town to face the Dodgers and Fernando. As the oft-told story goes, former Dodger Dave Stewart had thrown a no-hitter earlier in the day for the Oakland A’s, and as Fernando walked past a gathering of Dodger teammates who had just witnessed Stewart’s gem on TV, he said, “You just saw a no-hitter on TV, and now you will see one in person.”

Scioscia heard the quip after which went out and caught Fernando’s no-hitter, certainly one of two he caught in his profession (the opposite was by Kevin Gross two seasons later).

“It was an incredible moment,” Scioscia says. “He was not the Fernando of 1981. He had lost speed on his pitches, maybe some of his sharpness. But he was Fernando, still terrific.”

To commemorate Valenzuela’s profession and dying, the Dodgers are sporting uniform patches with the blue quantity 34 throughout this World Sequence. Simply in case any person forgets.

No person will.