In Gaza, the frontline is not only the place the bombs fall – it is the place the ambulances arrive.

When an Israeli airstrike hit a busy market in Gaza Metropolis at this time, folks have been queuing for flour.

Minutes later, medics have been selecting up physique elements. The our bodies have been heaved onto stretchers, mutilated limbs twisted unnaturally. Blood soaked the concrete.

Israel-Gaza newest: Netanyahu reportedly accepts US ceasefire plan

There are few paramedics left, and fewer ambulances. Gas is low. Gear is fundamental. They function in probably the most harmful locations on the planet, the place the medics themselves are now not spared.

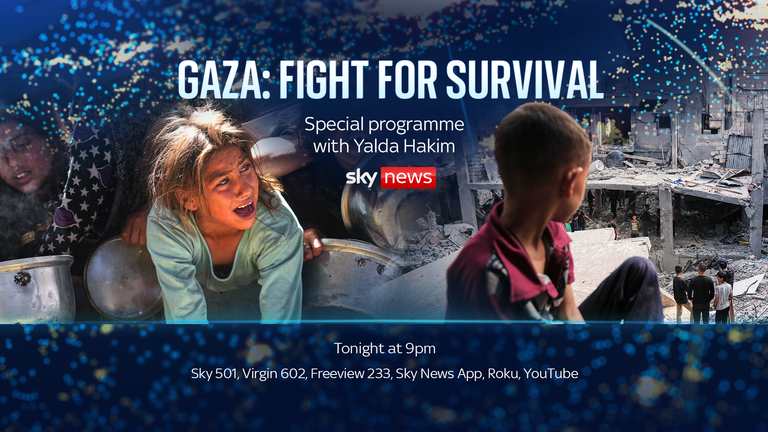

Picture:

‘We exit risking life and limb. We feature our coffins with us’, paramedic Hamdallah Ali Daher advised Sky Information.

“There is no safety”, says Hamdallah Ali Daher, a paramedic from Jabalia Camp in northern Gaza.

“When we respond to a strike, drones are still overhead. They targeted my colleague in one of our vehicles. You could be walking any day and get hit.”

The hazard is fixed. Daher describes how they function underneath the hum of drones, typically arriving at scenes the place smoke nonetheless rises from the wreckage. “We go out risking life and limb”, he says. “We carry our coffins with us.”

Spreaker

This content material is offered by Spreaker, which can be utilizing cookies and different applied sciences.

To point out you this content material, we want your permission to make use of cookies.

You need to use the buttons under to amend your preferences to allow Spreaker cookies or to permit these cookies simply as soon as.

You’ll be able to change your settings at any time by way of the Privateness Choices.

Sadly we have now been unable to confirm you probably have consented to Spreaker cookies.

To view this content material you should use the button under to permit Spreaker cookies for this session solely.

Allow Cookies

Permit Cookies As soon as

👉Hearken to The World with Richard Engel and Yalda Hakim in your podcast app👈

Considered one of his colleagues, Alaa al-Hadidi, was killed in a drone strike in December final yr. His fellow medics buried him. Israel has accused Hamas of utilizing ambulances to maneuver round Gaza disguised.

Picture:

A college used as a shelter was hit by an airstrike on Monday, killing dozens. Pic: Reuters

Wael Eleywa, one other paramedic, has labored all through the greater than 600 days of battle.

“What affects us the most is the children”, he says. “After a mission, you begin to imagine the injured children as your own relatives. These images stay with you and get mixed in your mind.”

Picture:

‘There is no psychological peace on this job’, paramedic Wael Eleywa advised Sky Information.

“Some of us have had to pull family members from the rubble.”

He describes responding to scenes the place tents have caught hearth after a strike – kids burned inside. “There’s no mental peace in this job”, he provides. “But the work still needs to be done.”

The battle, now nearing its twentieth month, has severely degraded Gaza’s emergency response community.

Many hospitals are now not functioning. The roads are harmful or impassable. The strikes come throughout the day and at the hours of darkness of evening. Fight zones shift every day.

“There is no protocol anymore”, Eleywa says. “We are medics in name, but the occupation doesn’t distinguish between civilians, or paramedics or anyone else. Even with permits, they detain or target us.”

Daher echoes the plea: “To all people, to all organisations – we need protection. We are trying to provide safety in a place where safety can’t exist.”

Regardless of the horror, there may be additionally resolve. “We lean on and support each other as colleagues”, says Daher. “Before the strikes, we’re often together laughing, trying to lift each other up. Then the call comes, and we go.”

Observe The World

Hearken to The World with Richard Engel and Yalda Hakim each Wednesday

Faucet to comply with

The medics converse with the matter-of-fact calm of those that have seen an excessive amount of. As they race between ruins and hospitals, they know that every shift may very well be their final.

“In this field of work”, Eleywa says, “we prepare for the worst, and go. Safety is out of reach.”