America was a nation divided, but that did not stop it from building parts of the James Webb Space Telescope in a red state and testing them in a blue one.

The European Union and Russia were facing off over Ukraine and other issues this year, but scientists from both sides will benefit greatly from the discoveries that could soon be within reach.

And while the pandemic snarled supply chains around the world, no lockdown could derail the telescope’s trajectory to the stars: Parts were assembled across multiple nations, then tested in the United States and the final product ended up on a launchpad in French Guiana before being hurtled into outer space on Christmas Day.

In some ways, the James Webb Space Telescope told a story seldom heard these days; the tale of nations coming together for a common ambition. At a time when countries are divided over climate change, migration and a disease that has killed millions, the spacecraft — launched to search for habitable planets and to seek out the earliest, most distant stars and galaxies — was a potent reminder that international cooperation on grand-scale projects was still possible.

“I like to think that science is a way to moderate some of the extreme situations that we have on this planet,” said Martin Barstow, a professor of astrophysics and space science at the University of Leicester in England, who oversaw the telescope’s mission control center. “And I’ve always seen space as an area where we cooperate, through all the trying times.”

With cooperation, however, has come competition as well. China, which did not participate in the project, is intending to launch its own space telescope expected to be a kind of competitor. China has also been teaming up with Russia on its own missions as the Russia-U.S. space alliance has come under strain because of political tensions between the countries.

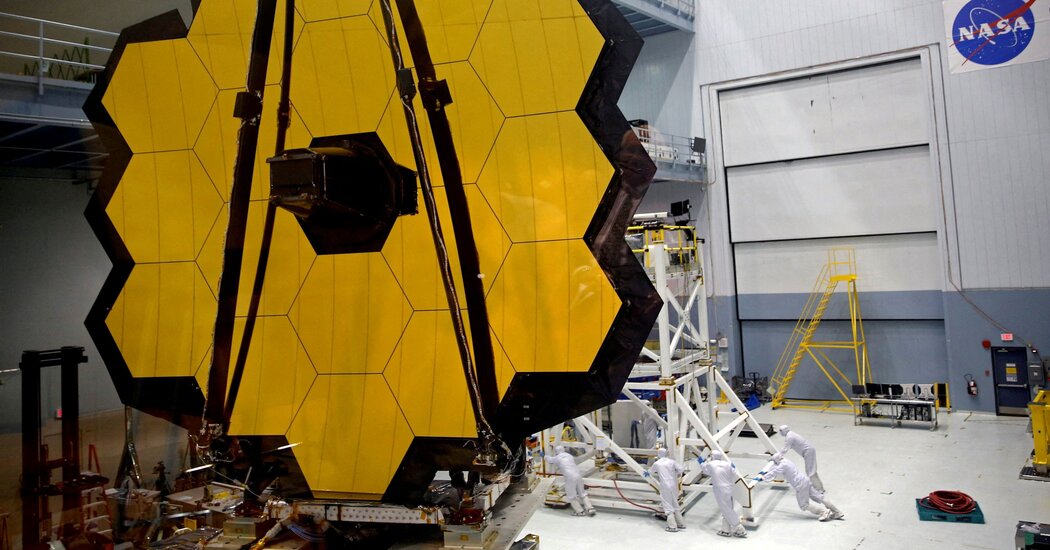

Still, the conception and launch of the telescope, which took more than 30 years, entailed not only the cooperation of scientists around the globe, but sharing the $10 billion cost, which was covered largely by the U.S. Unlike the Perseverance rover to Mars, a mostly American affair that launched last year and was overseen by the NASA, the James Webb Space Telescope was a joint venture of NASA, the Canadian Space Agency and the European Space Agency — the biggest and most expensive space-based observatory ever built.

Even as upheavals on both sides of the Atlantic altered the political landscape, none of it affected the telescope project. The work transcended the rise of Donald J. Trump in the United States, Britain’s withdrawal from the European Union and the growing popularity of nationalist movements in Europe, including many whose adherents have questioned the science of vaccines.

When the pandemic brought travel bans throughout the world, German scientists had to figure out how to remotely test parts of the telescope that were sitting in Redondo Beach, Calif.

“I had been coming frequently to Los Angeles and then you suddenly couldn’t do that,” said Oliver Krause of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Germany, who is working on the Webb telescope’s successor, which is already underway in California. He said the teams spent weeks devising workarounds.

Mr. Krause’s own contributions were key pieces of the engineering puzzle — the wheels that allow the telescope’s mid-infrared camera and spectrograph to switch between various modes. His team in Heidelberg, Germany, was chosen to build them because of its long expertise in the moving parts of telescopes.

“It’s key because if the wheel gets stuck in an intermediate position, you’ll suddenly have no light coming in,” he said, praising German engineering. Other parts of the telescope, like its sun shield, were built in locales like Huntsville, Ala.

Just as the parts of the telescope navigated borders and political divides, so did experts like Sarah Kendrew, an instrument and calibration scientist at the European Space Agency who is also an astronomer.

Ms. Kendrew helped create one of the key components of the telescope, the Mid-Infrared Instrument, or MIRI. The device is able to detect light from the mid-infrared region of the electromagnetic spectrum — unseen to the eye — and can reveal faint galaxies, stars in formation as well as planets orbiting other stars, known as exoplanets.

Ms. Kendrew’s work on MIRI began during a postdoctoral fellowship in the Netherlands in 2008. She then moved to Germany, where the instrument was tested, and to Britain, continuing work on MIRI and other astronomical instruments. Finally, in 2016, she moved to Baltimore, which became the telescope’s mission control center.

“Science is one of these areas where you have to learn to work across borders and across political divides,” she said shortly after she returned home from Kourou, French Guiana, a French territory in South America where she watched the liftoff of the telescope.

There seemed to be something hopeful about the launch itself, coming at the end of an extremely difficult year in a world desperate for good news. Watched in many countries, it harked back to the opening of the International Space Station two decades ago, or the early Apollo missions to the moon, when people tuned in to see the space race unfold around the globe.

“Everywhere in the world, people watched the launch of James Webb,” said Michaël Gillon, a Belgian astrophysicist involved with the project. “Even if they are in China or North Korea, it’s something that’s interesting for them. And the possibility of discovery interests people whatever their religion or political system.”

While scientists will be looking to the telescope to answer myriad questions about the universe, the one that has drawn the most excitement is something that humanity has long wondered: Will there be others looking back at us from the stars?

Mr. Gillon, who looks for signs of life on other planets, is assembling the team that may one day come back with an answer.

Using earlier telescopes, Mr. Gillon discovered seven Earth-size planets in the star system Trappist-1, in the constellation Aquarius. He named each after one of his favorite beers.

“We wanted to give a Belgian flavor to the project,” he joked.

In order to fully study Trappist-1, he organized a consortium of more than 100 scientists including ones from Morocco, Japan and the Netherlands, and pooled their resources to jointly research the star system.

“We may even be able to detect some traces of biological activity, which is really the holy grail of the field,” Mr. Gillon said.

The astronomer pondered for a moment the potential effect of finding life in the cosmos at a time when climate change and disease seem to threaten our collective future.

“It wouldn’t solve all our problems,” he acknowledged. “I still think this is something that would bring magic and the feeling of being human.”