In September 1994, the United States was on the verge of invading Haiti.

Jean-Bertrand Aristide, the country’s first democratically elected president, had been deposed in a military coup three years earlier. Haiti had descended into chaos. Gangs and paramilitaries terrorized the population — taking hostages, assassinating dissidents and burning crops. International embargoes had strangled the economy, and tens of thousands of people were trying to emigrate to America.

But just days before the first U.S. troops would land in Haiti, Joseph R. Biden Jr., then a senator on the Foreign Affairs Committee, spoke against a military intervention. He argued that the United States had more pressing crises — including ethnic cleansing in Bosnia — and that Haiti was not especially important to American interests.

“I think it’s probably not wise,” Mr. Biden said of the planned invasion in an interview with television host Charlie Rose.

He added: “If Haiti — a God-awful thing to say — if Haiti just quietly sunk into the Caribbean or rose up 300 feet, it wouldn’t matter a whole lot in terms of our interest.”

Despite Mr. Biden’s apprehension, the invasion went forward and the Haitian military junta surrendered within hours. Mr. Aristide was soon restored to power, and the Clinton administration began deporting thousands of Haitians.

Nearly a decade later, Haiti’s constitutional order would collapse again, prompting another U.S. military intervention, more migrants and more deportations. As rebels threatened to invade the capital in 2004, Mr. Aristide resigned under pressure from U.S. officials. A provisional government was formed with American backing. The violence and unrest continued.

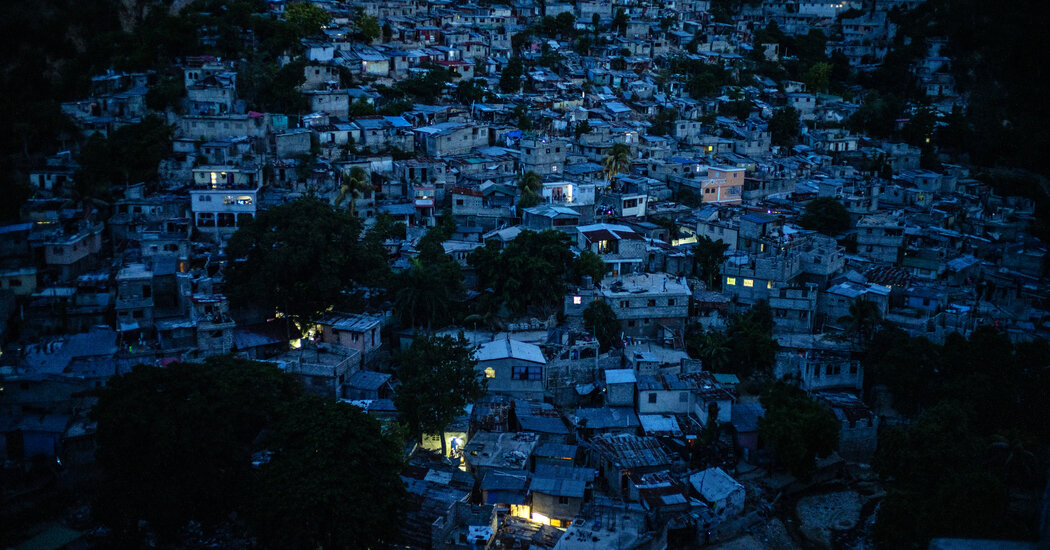

That cycle of crisis and U.S. intervention in Haiti — punctuated by periods of relative calm but little improvement in the lives of most people — has persisted to this day. Since July, a presidential assassination, an earthquake and a tropical storm have deepened the turmoil.

Mr. Biden, now president, is overseeing yet another intervention in Haiti’s political affairs, one that his critics say is following an old Washington playbook: backing Haitian leaders accused of authoritarian rule, either because they advance American interests or because U.S. officials fear the instability of a transition of power.

Making sense of American policy in Haiti over the decades — driven at times by economic interests, Cold War strategy and migration concerns — is vital to understanding Haiti’s political instability, and why it remains the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere, even after an infusion of more than $5 billion in U.S. aid in the last decade alone.

A bloody history of American influence looms large, and a century of U.S. efforts to stabilize and develop the country have ultimately ended in failure.

The American Occupation (1915-34)

The politics of slavery and racial prejudice were key factors in early American hostility to Haiti. After the Haitian Revolution, Thomas Jefferson and many in Congress feared that the newly founded Black republic would spread slave revolts in the United States.

For decades, the United States refused to formally recognize Haiti’s independence from France, and at times tried to annex Haitian territory and conduct diplomacy through threats.

It was against this backdrop that Haiti became increasingly unstable. The country went through seven presidents between 1911 and 1915, all either assassinated or removed from power. Haiti was heavily in debt, and Citibank — then the National City Bank of New York — — and other American banks confiscated much of Haiti’s gold reserves during that period with the help of U.S. Marines.

Roger L. Farnham, who managed National City Bank’s assets in Haiti, then lobbied President Woodrow Wilson for a military intervention to stabilize the country and force the Haitian government to pay its debts, convincing the president that France or Germany might invade if America did not.

The military occupation that followed remains one of the darkest chapters of American policy in the Caribbean. The United States installed a puppet regime that rewrote Haiti’s constitution and gave America control over the country’s finances. Forced labor was used for construction and other work to repay debts. Thousands were killed by U.S. Marines.

The occupation ended in 1934 under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Good Neighbor Policy. As the last Marines departed Haiti, riots broke out in Port-au-Prince, the capital. Bridges were destroyed, telephone lines were cut and the new president declared martial law and suspended the constitution. The United States did not completely relinquish control of Haiti’s finances until 1947.

Even after the United States had tired of Duvalier’s brutality and unstable leadership, President John F. Kennedy demurred on a plot to remove him and mandate free elections. When Duvalier died nearly a decade later, the United States supported the succession of his son. By 1986, the United States had spent an estimated $900 million supporting the Duvalier dynasty as Haiti plunged deeper into poverty and corruption.

Favored Candidates

At crucial moments in Haiti’s democratic era, the United States has intervened to pick winners and losers — fearful of political instability and surges of Haitian migration.

After Mr. Aristide was ousted in 1991, the U.S. military reinstalled him. He resigned in disgrace less than a decade later, but only after American diplomats urged him to do so. According to reports from that time, the George W. Bush administration had undermined Mr. Aristide’s government in the years before his resignation

François Pierre-Louis is a political science professor at Queens College in New York who served in Mr. Aristide’s cabinet and advised former Prime Minister Jacques-Édouard Alexis. Haitians are often suspicious of American involvement in their affairs, he said, but still take signals from U.S. officials seriously because of the country’s long history of influence over Haitian politics.

For example, after the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, American and other international diplomats pressured Haiti to hold elections that year despite the devastation. The vote was disastrously mismanaged, and international observers and many Haitians considered the results illegitimate.

Responding to the allegations of voter fraud, American diplomats insisted that one candidate in the second round of the presidential election be replaced with a candidate who received fewer votes — at one point threatening to halt aid over the dispute. Hillary Clinton, then the secretary of state, confronted then-President René Préval about putting Michel Martelly, America’s preferred candidate, on the ballot. Mr. Martelly won that election in a landslide.

A direct line of succession can be traced from that election to Haiti’s current crisis.

Mr. Martelly endorsed Jovenel Moïse as his successor. Mr. Moïse, who was elected in 2016, ruled by decree and turned to authoritarian tactics with the tacit approval of the Trump and Biden administrations.

Mr. Moïse appointed Ariel Henry as acting prime minister earlier this year. Then on July 7, Mr. Moïse was assassinated.

Mr. Henry has been accused of being linked to the assassination plot, and political infighting that had quieted after international diplomats endorsed his claim to power has reignited. Mr. Martelly, who had clashed with Mr. Moïse over business interests, is considering another run for the presidency.

Robert Maguire, a Haiti scholar and retired professor of international affairs at George Washington University, said the instinct in Washington to back members of Haiti’s political elite who appeared allied with U.S. interests was an old one, with a history of failure.

Another approach could have more success, according to Mr. Maguire and other scholars, Democratic lawmakers and a former U.S. envoy for Haiti policy. They say the United States should support a grass-roots commission of civic leaders, who are drafting plans for a new provisional government in Haiti.

That process, however, could take years.