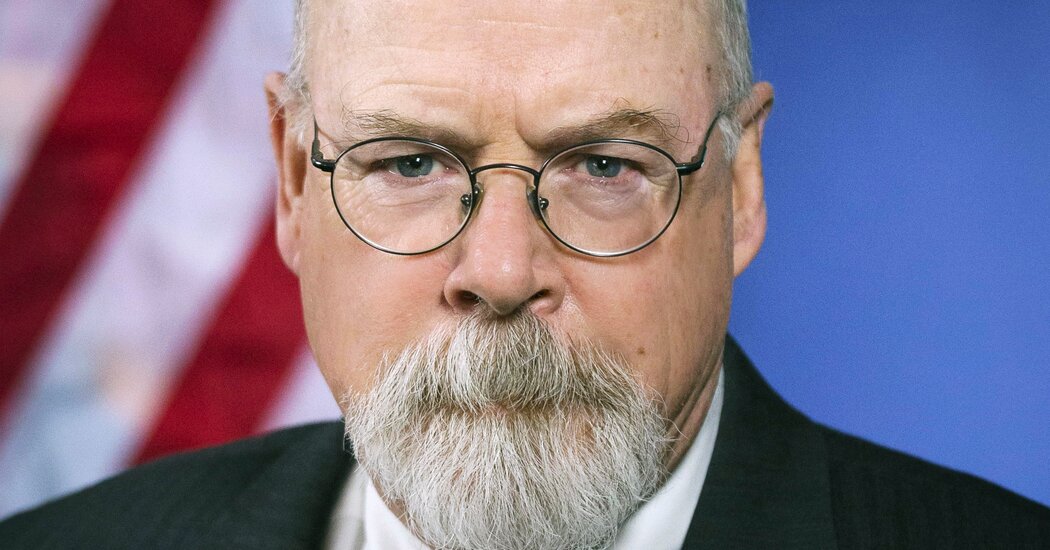

WASHINGTON — John H. Durham, the Trump-era special counsel scrutinizing the investigation into Russia’s 2016 election interference, distanced himself on Thursday from false reports by right-wing news outlets that a motion he recently filed said Hillary Clinton’s campaign had paid to spy on Trump White House servers.

Citing a barrage of such reports on Fox News and elsewhere based on the prosecutor’s Feb. 11 filing, defense lawyers for a Democratic-linked cybersecurity lawyer, Michael Sussmann, have accused the special counsel of including unnecessary and misleading information in filings “plainly intended to politicize this case, inflame media coverage and taint the jury pool.”

In a filing on Thursday, Mr. Durham defended himself, saying those accusations about his intentions were “simply not true.” He said he had “valid and straightforward reasons” for including the information in the Feb. 11 filing that set off the firestorm, while disavowing responsibility for how certain news outlets had interpreted and portrayed it.

“If third parties or members of the media have overstated, understated or otherwise misinterpreted facts contained in the government’s motion, that does not in any way undermine the valid reasons for the government’s inclusion of this information,” he wrote.

But even as he did not acknowledge any problem with how he couched his filing last week, Mr. Durham said he would make future filings under seal if they contained “information that legitimately gives rise to privacy issues or other concerns that might overcome the presumption of public access to judicial documents.”

Former President Donald J. Trump has seized on the inaccurate reporting to declare that there is now “indisputable evidence” of a Clinton campaign conspiracy against him — and to suggest that there ought to be executions. Mr. Trump, Fox News hosts and others have also criticized mainstream journalists for not covering the purported revelation.

The dispute traces back to a pretrial motion in the case Mr. Durham has brought against Mr. Sussmann accusing him of making a false statement during a September 2016 meeting with the F.B.I. where he relayed concerns about possible cyberlinks between Mr. Trump and Russia. The bureau later dismissed those as unfounded.

Mr. Durham says Mr. Sussmann falsely told the F.B.I. official he had no clients, but was really there on behalf of both the Clinton campaign and a technology executive named Rodney Joffe. Mr. Sussmann denies ever saying that, while maintaining he was only there on behalf of Mr. Joffe — not the campaign.

Several sentences of the filing recounted a second meeting, in February 2017, where Mr. Sussmann had presented different concerns about odd internet data and Russia to the C.I.A., which came from the same cybersecurity researchers who developed the suspicions he had presented to the F.B.I.

At the C.I.A. meeting, Mr. Sussmann shared concerns about data that suggested that someone using a Russian-made smartphone may have been connecting to networks at Trump Tower and the White House, among other places.

Mr. Sussmann had obtained that information from Mr. Joffe. The court filing also stated that Mr. Joffe’s company, Neustar, had helped maintain internet-related servers for the White House, and accused Mr. Joffe — whom Mr. Durham has not charged with any crime — and his associates of having “exploited this arrangement” by mining certain records to gather derogatory information about Mr. Trump.

In the fall, The New York Times had reported on Mr. Sussmann’s C.I.A. meeting and the concerns he had relayed about the data suggesting the presence of Russian-made YotaPhones — smartphones that are rarely seen in the United States — in proximity to Mr. Trump and in the White House.

But over the weekend, the conservative news media treated those sentences in Mr. Durham’s filing as a new revelation while significantly embellishing what it had said. Mr. Durham, some outlets inaccurately reported, had said he had discovered that the Clinton campaign had paid Mr. Joffe’s company to spy on Mr. Trump. But the campaign had not paid his company, and the filing did not say so. Some outlets also quoted Mr. Durham’s filing as using the word “infiltrate,” a word it did not contain.

Most important, the coverage about purported spying on the Trump White House was premised on the idea that the White House network data involved came from when Mr. Trump was president. But Mr. Durham’s filing did not say when it was from.

Lawyers for a Georgia Institute of Technology data scientist who helped analyze the Yota data said on Monday that the data came from the Obama presidency. Mr. Sussmann’s lawyers said the same in a filing on Monday night complaining about Mr. Durham’s conduct.

Mr. Durham did not directly address that basic factual dispute. But his explanation for why he included the information about the matter in the earlier filing implicitly confirmed that Mr. Sussmann had conveyed concerns about White House data that came from before Mr. Trump was president.

The purpose of the earlier filing was to ask a judge to look at potential conflicts of interest on Mr. Sussmann’s legal team. Mr. Durham included those paragraphs, he wrote, in part because one of the potential conflicts was that a member of the defense had worked for the White House “during relevant events that involved” the White House.

The defense lawyer in question is Michael Bosworth, who was a deputy White House counsel in the Obama administration.

Separately on Thursday, lawyers for Mr. Sussmann filed a pretrial motion asking a judge to dismiss the case.

They argued that even if Mr. Sussmann did falsely say at the F.B.I. meeting that he had no client — which they deny — that would not rise to a “material” false statement, meaning one affecting a government decision. The decision facing the F.B.I. was whether to open an investigation about the concerns he relayed at that meeting, and it would have done so regardless, they said.

Mr. Durham has said Mr. Sussmann’s supposed lie was material because had the F.B.I. known that he was acting “as a paid advocate for clients with a political or business agenda,” agents might have asked more questions or taken additional steps before opening an investigation.