After I started studying Elaine Castillo’s Moderation, a brand new American novel concerning the psychological harm of on-line moderation, I needed to pause.

I’d learn novels that confronted tough materials earlier than, however this one blurred the road between bearing witness and re-enacting ache.

The e-book follows Girlie, a content material moderator for a social media big whose work requires her to observe and delete the web’s most violent footage. Castillo threads this labour via a broader story of tech exploitation, immigration and the best way empathy turns into a marketable ability.

I put it down, deeply uncomfortable, but in addition alert to the query: the place is the road between crucial confrontation and pointless hurt?

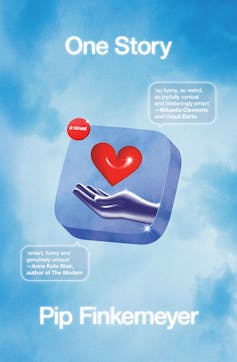

Overview: One Story – Pip Finkemeyer (Ultimo)

That query lingered as I turned to Australian novelist Pip Finkemeyer’s One Story, a novel excited about energy and efficiency that phases its discomfort via satire relatively than shock. If Moderation shows to readers the brutality of what’s seen, One Story unsettles by displaying us how violence can conceal behind language – in self-branding and the efficiency of care.

Set between Silicon Valley, Bali and the digital ether of on-line mythmaking, One Story unfolds as a collage of interviews, transcripts, on-line threads and recollections from those that knew – or thought they knew – its central determine, Dot van Jensen.

Dot is the CEO of the eponymous storytelling platform. One Story is an app that guarantees to unify international narratives right into a single day by day story, “a sort of algorithmic scripture capturing the emotional pulse of the world.”

She can also be a grasp manipulator, narcissist, lover and mom: half tech visionary, half public scandal.

Tech’s golden woman

The novel opens, characteristically, in self-mythologising mode.

“I was tech’s golden girl with golden hair,” Dot boasts. “CEO is my blood type.”

In a number of pages, she establishes herself as considered one of Finkemeyer’s most unreliable creations – a girl who, just like the platform she builds, believes narrative is each forex and confession.

Her voice is slick with the idioms of self-optimisation: “Efficiency is meaningful,” she tells a lover mid-kiss. “My no-phones policy meant the only way to talk to me was face-to-face, but I didn’t identify as a person who should have to go to meetings.” It’s the rhetoric of an individual who confuses boundaries with branding.

Finkemeyer’s satire is unrelenting. The early chapters, advised in Dot’s personal voice, mimic the cadence of company keynotes and startup manifestos, however laced with absurd self-awareness. The absurdity works as a result of it’s so recognisable.

The slogans sound like motivational copy taken from LinkedIn posts: “We make technology for human bodies;” “We’re not asking for more of your time – we’re asking for less.” However behind the polished aphorisms, there’s one thing genuinely sinister: the commodification of intimacy.

When One Story is launched, the revealing feels extra like a sermon than a product demo. Dot’s lover and co-founder, Rae, takes the stage in San Francisco to current the machine – a handheld coronary heart, glowing with textual content – declaring:

One story a day. All it is advisable know of the world, proper within the palm of your hand. Then the present of your life again.

The pitch guarantees connection however enacts discount, compressing the world’s chaos right into a single paragraph. Finkemeyer’s writing right here is sharp and rhythmic, the prose echoing the tech-world fetish for readability whereas exposing its ethical vacancy.

Want turns into technique

Dot’s narcissism might simply have develop into one-dimensional, however Finkemeyer provides her depth via contradiction. She is a Dutch-born immigrant who as soon as cleaned practice station flooring in Spain and raised her son, Jon, alone. She’s additionally a queer lady who weaponises appeal and sexuality as types of dominance.

When she remembers her early relationships – “We had met in the rain at the bus stop […] we were fourteen” – her tenderness is all the time filtered via the language of transaction. Love turns into labour and want turns into technique.

Even her erotic creativeness folds again into ambition. “I saw that it was my job to bring the feminine to the tech world,” she claims, “to spread my femme energy all over everyone inside, without them suspecting a thing.” This conflation of seduction and messianic mission underpins the novel’s satire.

Dot treats intimacy as one other medium for management. The passages depicting her affair with Rae are particularly uncomfortable of their precision. Rae yearns for real connection, however Dot instrumentalises her affection.

“I could give her companionship, stewardship, mentorship,” Dot displays, “even, when she desired it, sexual intimacy. But it would always be fleeting, in the moments between when the real work was being done.”

The bluntness of this confession – half self-awareness, half sociopathy – crystallises the e-book’s ethical core: the concept emotional labour has been subsumed by the logic of productiveness.

The novel’s construction reinforces this unease. Every half shifts perspective, from Dot’s self-narration, to Rae’s testimony in a damning documentary, to Jon’s retrospective reflections and at last to the collective voice of “We/Us,” the staff of One Story.

This multi-voiced design mirrors the saturation of mediated storytelling within the digital age, the place each narrative is filtered via one other. Finkemeyer makes use of these shifting kinds to check the reliability of voice itself.

Rae’s part, introduced as a transcript from the exposé that topples Dot, captures the collapse of authenticity into efficiency.

“Dot seduces everyone,” Rae says. “She’s a master of seduction … funny weird, but not funny ha-ha.”

Her recollections oscillate between admiration and repulsion, revealing how charisma capabilities as a type of coercion. When she describes the early prototypes of One Story – jokes fed into an algorithm to generate “content” for the wealthy – the satire feels painfully believable.

Finkemeyer understands that what we now name “innovation” usually originates in cringe.

Essentially the most chilling flip within the e-book comes when the collective voice of the corporate takes over. “We were always watching the three of them,” the staff recall, “trying to figure out who loved whom the most.”

Their admiration transforms into complicity. They converse like a Greek refrain, euphoric and self-justifying:

All of us subscribed to the concept the world was changing into a greater place. And since we labored at One Story, we have been on the correct facet of historical past.

Finkemeyer renders this company refrain voice with disturbing precision, exposing how ideology seeps into syntax.

Confession as violence

All through, the novel performs with the concept confession itself is usually a type of violence. When its Campana Analitica scandal breaks, the corporate’s PR machine deploys the identical placid, tech-bro tone used to explain their mission.

Requested by a documentary producer concerning the human value of their knowledge leaks, Rae replies with deadpan sincerity: “We take user privacy seriously and have set up a taskforce …” The irony lands onerous as a result of it’s so acquainted, in its absence of feeling and routinisation of hurt.

(Campana Analitica is a thinly veiled parody of the Cambridge Analytica scandal, through which a political consulting agency harvested Fb consumer knowledge to control voter behaviour.)

In its closing chapters, One Story turns into more and more self-reflexive, blurring the road between the documentary’s gaze and Dot’s personal try to narrate herself. As fragments of her story proliferate on-line, hypothesis replaces fact. Finkemeyer lets the noise construct to an nearly comedian pitch, displaying how, in a world saturated with storytelling, the self can vanish beneath its personal narration.

But the novel resists pure cynicism. Beneath its biting humour and relentless irony is a sustained enquiry into what it means to stay ethically in a tradition that monetises empathy.

Dot’s firm guarantees “one story a day” as if emotional consideration might be quantified. However the narrative that emerges from the novel’s fragments – Dot’s childhood poverty, her fraught relationship together with her son, Rae’s idealism corroded by proximity to energy – suggests one thing extra tender. Finkemeyer’s satire by no means forgets that these performances of self come up from eager for recognition and for management over one’s story.

Finkemeyer’s expertise lies in her capability to make narcissism really feel each grotesque and magnetic. The novel’s humour – its deadpan send-ups of startup jargon, its parodies of TED-talk sincerity – is so attuned to the rhythms of up to date speech that it usually feels documentary itself. Studying it’s like scrolling via a feed that’s equal elements confession and commercial.

Nonetheless, there are moments the place the novel’s polish threatens to easy over its emotional stakes. Finkemeyer’s management is so deft that her irony often blunts the ethical power of the work.

The narrative’s self-aware commentary on storytelling as capital can really feel overbearing. However maybe this, too, is deliberate. The exhaustion we really feel studying Dot’s voice, the repetition of slogans and spin, mimics the burnout of inhabiting digital life. Finkemeyer doesn’t simply signify the eye economic system; she recreates its seductions and its fatigue.

One Story is a novel form of satire: one that’s amusing, but additionally profoundly unhappy. Its characters are trapped not by villains however by financial, technological and emotional techniques that reward efficiency over sincerity. Dot, Rae and Jon every mistake narrative for connection. Their tragedy will not be that they’re monstrous, however that they’re strange.

As Dot says early on, defending her personal fable: “The only thing I’m guilty of is becoming the person they so desperately wanted me to be.”

Finkemeyer brings us to a spot of uneasy recognition. The cringe we really feel at Dot’s vanity, at Rae’s complicity, on the workers’ blind devotion is the heartbeat of the novel. It measures how totally our lives have develop into entangled with the equipment of story.

I didn’t end Moderation. But I completed One Story with an identical unease: not at what it depicted, however what it revealed.

Finkemeyer exposes how energy hides behind aesthetics and the way empathy may be algorithmic. On the earth of One Story, every part – together with discomfort – is materials.![]()

Caitlin Macdonald, Physician of Philosophy (English) / PhD graduate / Researcher, College of Sydney

This text is republished from The Dialog underneath a Artistic Commons license. Learn the unique article.