By Lucia Matuonto

When did you realize you wanted to pursue writing as a career?

Life is always benevolent. Before we ever get inspired to fulfill any dream, life has already set up all the opportunities and support we need to make that dream come true. The week I decided that my destiny was to become an author, my 8th grade English teacher gave my class a unique assignment: we were to do any creative project we wanted related to literature. As soon as I received that assignment, I knew I would write my first story. Two weeks later, I turned in a story of more than 50 pages. I suspect my teacher’s excited reaction at seeing that thick block of paper must have felt like a comedian getting his first laugh. Her response, and the generous comments she gave my work, fueled my enthusiasm for my dream career.

I changed high schools when my family moved across the country. Left with plenty of empty evenings, I used that time to set an ambitious goal: I wrote my first book before I graduated. My gracious senior English teacher, Mrs. Collings not only read the novel, but she sacrificed several of her lunch periods to discuss the work with me. I submitted the book to New York publishers but didn’t start getting any of my books published for many years. That first novel remains unpublished. Intriguingly, an interviewer recently asked me about that book. When I told her the premise, she encouraged me to pull it out and start submitting it again.

Can you describe your typical writing process? Do you have any specific routines or habits that help you write?

I just write. As a former literature teacher professor, and now writing coach, I tell students and clients that the biggest obstacles to completing any draft are planning too much and revising too soon. For many aspiring authors, too much planning is simply a way of delaying that courageous leap into starting the first draft. Editing while writing the first draft is fatal. Writers don’t know what to edit until they’ve completed the first draft because—for fiction and nonfiction—every element of the work has to build toward a satisfying conclusion. It usually takes writing the first draft to discover what your characters in fiction and your ideas in nonfiction really want to convey. At first, a book is as much of a mysterious journey for the writer as it is for the reader.

How do you come up with the ideas for your stories or books?

My goal is to be open to the creative process. In that frame of mind, I don’t take credit for coming up with ideas for my books. The ideas come to me. If I’m curious about a topic, I’ll start reading. If I have questions that I don’t find answered in other writers’ works, I often feel inspired to write them myself. For example, when I was a high school literature teacher decades ago, some classes had to write biographical essays about any author in their literature textbook. At the time, older books about Danish author Isak Dinesen were out of print, and Judith Thurman’s excellent but lengthy National Book Award-winner, Isak Dinesen: The Life of a Storyteller was too daunting for students to even pick up. So, I wrote Isak Dinesen: Gothic Storyteller, a YA biography of her life for students researching her for that assignment.

More often than not, I will get a spiritual inspiration that leads to a new book. One night I had a dream to live the next 365 days as if I would never experience those dates again. I wasn’t necessarily told I would die in a year, but I was to live as if I might, packing in everything I wanted to do for myself and others so that, whenever I did reach the end of my life, I would have left nothing undone. I jumped out of bed that morning and began living what has come to be known, My First Last Year. The record I kept of that life-shaping year became that book.

What do you find most challenging about the writing process, and how do you overcome those challenges?

I love a challenge. Recently I was working on my fourteenth revision of my YA novel, No Stranger Christmas and was exhausted! Sometimes my brain would flash some very unhelpful thoughts. One was, I must be getting older because this revision has been very difficult. Since my first draft of over 600 pages, I had honed and tweaked and pared it down to less than half that total. When I stepped back to see what I had accomplished, I realized I was running a metaphoric marathon, and was actually using creative muscles and sustaining momentum in ways I never had before. In that moment of realization, the challenge shifted from wearing me out to invigorating me. As if getting my second wind with the finish line in sight, I sped through the rest of that revision (and one more after that). It has resulted in what I hope is one of the strongest books of my career.

Thanks to this lesson, I don’t recommend overcoming challenges. I invite people to dive into them and stay the course until they build new muscle and learn who they really can be. We’re always capable of doing more and being more than we believe about ourselves before we accept the challenge.

Could you share a bit about your latest work? What was the inspiration behind it, and what do you hope readers will take away from it?

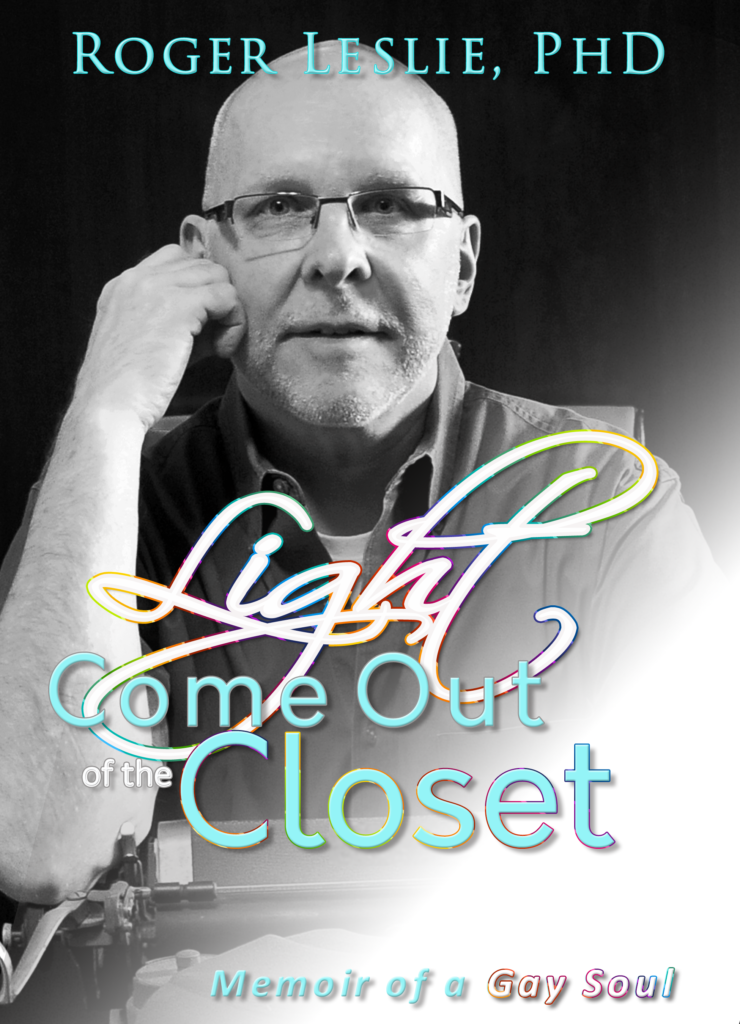

My heart goes out to those LGBTQ teens who feel isolated and lonely, or whose focus on figuring out their soul or just surviving in environments hostile to them keeps them from utilizing their natural talents. Those hostile environments include school, church, and sometimes their own home. I explored my unique journey out of that environment in my latest book, Light Come Out of the Closet. Now I’ve written No Stranger Christmas to shine a light of hope for those readers in any such environment. I also wrote it in such a way that I hope, adults who want to better understand how difficult it is to navigate those struggles can. Even more ambitiously, I hope adults who have negative religious preconceptions about gender or sexuality will discover that, as one character says in the novel, “God doesn’t make mistakes. You know that, don’t you?”

Do you have a favorite character from your own books, and if so, why is that character special to you?

I love many of my characters, but when I teach writing courses, one character I often use as an illustration of the magic of the creative process is Russell from the novel, Drowning in Secret. I wrote the book more than twenty years ago, so I was still on a high learning curve about writing fiction.

I created Russell as a minor character with one purpose. Early in the novel, he was a foil to Mark, his friend, and one of four main characters in the book. The narration follows each of four characters in the same family: the mom, the dad, the sister, and Mark. They’re all drowning in their own secrets, not realizing how parallel their experiences are with the rest of their family. I wrote Russell’s scene and thought, Okay, he’s gone. I don’t need him anymore.

As I wrote a later chapter in that first draft, Russell came back. I thought that was strange, but he worked well in the scene, so I left him in. A few chapters after that, he came back.

By this time Russell seemed like a defiant child who would not do what I wanted him to: get out of my novel. When he came back again, I wrote one of the pivotal scenes: I actually drowned him. That chapter ends with lifeless Russell lying at the side of the pool. I left my writing desk that evening dusting off my hands thinking, Good, he’s gone.

I couldn’t believe what happened when I started writing the next chapter. Another character ran out to the pool and revived him! That’s when I stopped fighting Russell and began trusting that maybe my characters knew more about what the novel needed than I did.

Russell isn’t in much more of the novel, but he shows up at the end. Turns out, he is the one who articulates the theme of the entire novel. Once I read what he said, I thought, Of course! My four main characters are so steeped in their own troubles and delusions, they would need someone outside their family to see and point out the issue that’s keeping them all adrift. I also realized that this insight had more power coming from a character as young as Russell. His innocence and intelligence make the expression of that theme palatable.

How do you handle criticism or negative feedback about your writing?

My general philosophy on life, much of which I explain in My First Last Year, includes the analogy that life is a prism. We’re all looking at the same thing, but from a different facet of the prism. As such, one person may look at one of my books and love it, another may not. What’s the difference? Their facet of the prism.

When I was a classroom teacher, I started a literature lesson by drawing a human figure and, a little way away from it, a book. Then I asked students, “Where does literature exist?” At first, they’d answer, “In the book.” After a little more discussion, they’d usually change their minds. “No, it’s in the mind of the reader.” After deeper exploration, they would conclude that literature exists in the space between the book and the readers.

Readers come to any book with all their own personality traits, their life experiences, their hopes and ideals, and their prejudices. When someone doesn’t like a quality work of art (and I aspire to ensure that all my books meet that demand), then their issues with it are about their response to the book more than the book itself.

If authors believe their positive reviews, then it’s only fair that they believe their negative ones. As a rule, I don’t read reviews of my books. By the time the book has been published, I have had it professionally edited by someone in the industry I respect and have received feedback or critiques from beta readers. After I’ve made all the revisions based on their comments, I have done with the work everything I know to do to make it the most excellent I can. Reviewers share their responses to my book after it’s ready to be launched or after it’s published. At that point, there’s nothing I can do to make that published work better. If my publicist reads a review that she thinks can help me do better next time, she’ll share that with me. In that constructive context, the feedback is helpful. Unless a comment is helpful, what use does it serve? So, I take to heart the feedback that can help me do better next time and protect my heart from the sting of unkind, unconstructive comments.

What advice do you have for aspiring writers who are looking to publish their first book?

I implore all writers to make certain their book meets the standards of excellence all readers deserve. While self-publishing and entrepreneurial publishing have opened the world of books to many authors who otherwise would not find success, it also enabled substandard products to enter the marketplace.

Writers have three general publishing options: traditional, entrepreneurial, and hybrid. With traditional publishing, authors submit their work for publishing consideration. When it’s selected, the publishing house pays the cost for putting the book in print. Because they’re taking the financial risk, they also usually get 90% of the royalties.

Entrepreneurial publishing has the authors paying to publish their books, but they get the royalties. This path has a high learning curve and requires hiring companies to complete some tasks, such as typesetting and uploading files to online booksellers. If you don’t know the business, it’s hard to know which companies will do it well for a fair price. Even though, theoretically, entrepreneurial authors get 100% of their book royalties because they are the publisher, online booksellers and distributors take a large portion of that profit. Early on, authors may not see much more in royalties than if they traditionally published.

In between those two options is hybrid publishing where the publisher and author share in the expense of publishing the book and determine a split on royalties. Thanks to the Independent Book Publishing Association (IBPA), hybrid publishers have standards they must meet for publishing excellence.

To all authors, I say the first step is to make sure you have a solidly written manuscript that adds something new to the body of knowledge currently available in nonfiction or a resonant, dynamic new voice in fiction. That process includes hiring an excellent editor to provide feedback. Often it also helps to have a qualified writing coach to help through the revision process. Writers should secure those professionals before they even consider publishing.