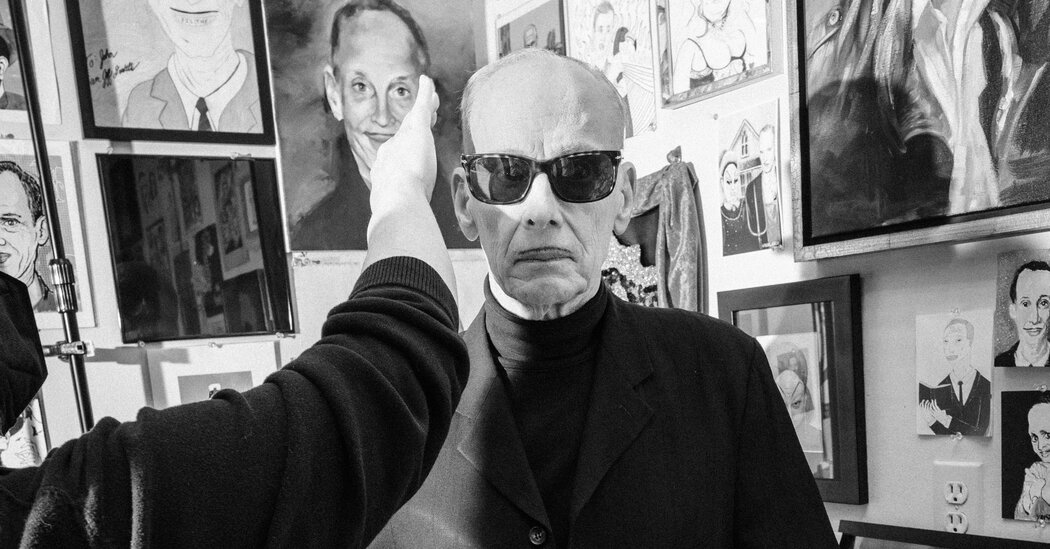

BALTIMORE — John Waters was leading a delegation from the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures — in for the week from Los Angeles — on a tour of his home of 32 years, cluttered with film artifacts and kitschy curios and tucked behind trees on a quiet corner five miles from this city’s waterfront.

There was much to see: the electric chair from his 1974 dark comedy, “Female Trouble” in the entryway. A birth certificate for Divine, the 300-pound cross-dresser who played the “filthiest person alive” in “Pink Flamingos,” hanging in a basement room piled with mementos. The mimeographed poster for the 1966 premiere of “Roman Candles,” retrieved from a stack of boxes.

“Hand me that leg of lamb,” Waters asked an assistant as two curators and the museum director followed him up the narrow stairs, through a doorway and into his cramped two-room home office — one room for “my writing and thinking” and one for, as he put it, selling. He was offering for consideration a favorite artifact from his moviemaking career: the (rubber) leg of lamb that Kathleen Turner used as a murder weapon in a particularly gruesome scene from “Serial Mom.”

For decades, Waters was famous for pushing the boundaries of taste back when there were real boundaries of taste (enforced by entities like his one-time tormentor, the Maryland State Board of Censors), including the notorious final scene in “Pink Flamingos,” which involves dog excrement. William S. Burroughs called Waters the “Pope of Trash,” and he meant that as a compliment.

Next summer, Waters, who is 76, is being honored by the establishment he has flamboyantly provoked for over 50 years. He will be the subject of a sprawling 11,400-square-foot exhibition at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures, the museum celebrating Hollywood that opened last year. With this exhibit, the Academy is making clear that its curatorial appetite goes beyond R2-D2 and Dorothy’s ruby slippers.

This may not be easy. The Academy Museum has planted a flag as a family and tourist destination, which is not precisely the John Waters fan base. Notwithstanding the name of the exhibition — “Pope of Trash,” of course — Bill Kramer, the museum’s director, said a sign might be put at the entryway to warn the young and the squeamish.

“We don’t want to do anything that will alienate our audiences,” Kramer said, pulling up a chair next to Waters in his living room. “We are going through the design process now, and through that process, we will ensure that the exhibition will not be watered down, but will also be an exhibition that all ages can experience.”

“Which is a challenge,” Waters interjected.

“Which is a challenge,” Kramer agreed.

Waters has come quite a distance since 1973, when Variety described “Pink Flamingos” as “one of the most vile, stupid and repulsive films ever made.” His subsequent movies — “Polyester,” starring Tab Hunter; “Cry-Baby,” with Johnny Depp; and “Pecker,” with Patricia Hearst, to name a few — have become cult favorites, some still drawing crowds at midnight showings. “Hairspray,” his 1988 comedy, became a Broadway musical that won eight Tony Awards. Now Waters will join the ranks of Spike Lee, Pedro Almodóvar, “The Wizard of Oz,” and “The Godfather,” as the subject of an exhibition at the Academy museum.

“People will see irony in it, definitely,” said Waters. “My films, certainly in the beginning, got no good reviews, were censored, but people always came. Just crazy people came.”’

“And did any of them get nicer?” Waters said of his films, warming to the subject. “No! They all got accepted over the years, which just meant American humor has changed for the better. I think that we got used to embracing all kinds of films if they were extreme and had style about them.”

If he is right about that — and he very well might be — that should make life easier for the curators as they spend the next year deciding which works to highlight, how much to present in gory, scatological or X-rated detail, and how much to leave to viewers’ memories and imagination.

Among the items they are considering: The barf bags, protectively handed to audience members for showings of “Pink Flamingos.” The hand-held camera Waters used in “Eat Your Makeup” to film the re-enactment of the Kennedy assassination on his parents’ front lawn, to the horror of neighbors, with Divine playing Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. A list of live bugs, a German cockroach and a Dragonfly Nymph among them, that the actor Johnny Knoxville was willing to put in his mouth for the 2004 film, “A Dirty Shame.”

And there is the depiction of shoes painted by the glue-sniffing Baltimore foot stomper while serving prison time in “Polyester.” The scratch-and-sniff cards embedded with stomach-turning odors that were handed to patrons at “Polyester” so they could experience the film with their noses, as well as their eyes. That leg of lamb.

But those kinds of decisions are months away. The exhibition is in the planning stages. Before arriving in Baltimore, the curators, Jenny He and Dara Jaffe, spent months combing through the Waters archives at Wesleyan University, with considerable success. “In ‘Hairspray,’ at the end, Debbie Harry is wearing this towering wig that has this explosive device,” Jaffe said. “We asked everyone and no one knew what happened to it. It turns out it was at Wesleyan the whole time. We found it in a box in a corner.”

“Dara and I started jumping up and down,” said He.

Here in the city that has defined Waters’s career and life, they traipsed through his house, itself something of a museum, before driving to his studio and his office as they considered which of the 881 items that have made their preliminary list (“I’m a hoarder,” Waters said) merits display.

“Jenny, we should measure this,” Jaffe said, taking out a tape after spotting a “Maryland State Board of Censors” seal painted by a fan and sent to Waters in his office, a testimony to the time the board forced Waters to cut a scene from “Female Trouble.” Waters made the censors give him a receipt for the snippet of film he cut off the reel and handed over.

When they arrived at his studio, the curators huddled with Waters to share one idea for the entryway to the exhibition.

“So we know that you want people to get a bit of a shock when they first walk in,” Jaffe said, as Waters nodded. “And we know how much you love showmanship and gimmicks.” The idea, she said, would be to create the inside of a church, with a montage of Waters films spooling near the altar. The pews — “the movie seats” — would be equipped with hidden buzzers to “give them a literal shock” as they sat down, she explained.

“Can you make that work?” Waters exclaimed. “That would be great!”

This exhibition may seem like something of a gold retirement watch for Waters, a belated recognition of his contribution to cinema and culture over the decades. It has been 18 years since Waters made his last movie — “A Dirty Shame,” which was rated NC-17. But he has since been paid to write three sequels to “Hairspray,” none of which ultimately received a studio green light. He has also continued to develop a long-gestating children’s Christmas movie called “Fruitcake.”

Waters is hardly retiring, though. He has been traveling the country promoting his first novel, “Liarmouth: A Feel-Bad Romance,” (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2022), and recently had a cameo in “The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel.” He is in a new advertising campaign for a Calvin Klein fashion line for Pride Month. He still has the pencil mustache, which he freshened up throughout the day.

Museum officials could barely keep up with him as he clambered up and down the steps of the four-story house, before jumping into a rented Cadillac (his own car is being driven by an assistant to Provincetown, where he will spend the summer) to lead a cavalcade on the drive to his studio and his office.

In truth, Waters has become part of the entertainment establishment. He is a member of the Academy, sponsored by the filmmaker David Lynch, himself a bit of an envelope-pusher. (“And I take my duties seriously,” he said of being an Oscar judge. “I watch everything.”) “Hairspray” was rated PG. And in another sure sign of success, Waters is surrounded by a coterie of assistants as he moves through his day. “I need three assistants to turn on a TV,” he said.

Kramer, who this week was named the chief executive of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, proposed the exhibition in March 2020. Waters agreed, and the curators headed out for a scouting visit that month. Because of the pandemic, this was the first time Jaffe and He have been back to Baltimore. “I’ve kept this secret for a long time,” Waters said.

The show will introduce the Waters canon to audiences unfamiliar with his work, but the base is likely to be his loyal followers, the ones who went to his movies before they were legitimized in festivals and revival houses, and who attended Camp John Waters, his sold-out adult summer camp in Kent, Conn.

“My audience was always humorous and they were always a little angry, but they were always movie buffs, they had a sense of humor about themselves and they made fun of their own taste in a way they embraced tastes that others would be against,” Waters said. “My audience was not just gay or straight; it was bikers, or it was all people that didn’t fit in; even in their own minorities they had trouble, and there was my target audience.”

Waters has never lived in Los Angeles, but was a guest at the red-carpet opening of the museum last year — sharing the spotlight with Cher and Lady Gaga. “I was just amazed — who would have ever thought all these things would happen?” Waters asked. He waited a beat. “And the answer is — me.”