They are a spiky, ambitious lot. We encounter the poet John Ashbery, to whom Schloss complained about being called “semiabstract” by a critic. “‘Isn’t all life semi?’” he replied consolingly. And the composer Elliott Carter, who sneered of folk music’s influence on modern urbans: “We are not shepherds. We are not coming out of the hills. We are not folk.” The dancer and choreographer Merce Cunningham rears up “like a furry old faun”; the gallerist Leo Castelli has a Felix Unger-ish fastidiousness.

Explore the New York Times Book Review

Want to keep up with the latest and greatest in books? This is a good place to start.

Schloss writes of a time, incredible as it may seem now, when painters in New York had the clout of movie stars. (These days, maybe even movie stars no longer have the clout of movie stars.) The Bob De Niro she gossiped with over a temperamental kerosene stove on the street was the actor’s father. Franz Kline, another abstract expressionist, with whom she danced the tango, “had a sort of Bogart-like cool and melancholy.” Strolling downtown alongside Willem de Kooning, the Dutch painter, leader of this set, “was like walking with Clark Gable in Hollywood.”

De Kooning and his wife, Elaine, a.k.a. “Queen of the Lofts,” are among the more completely filled-out figures in a collection of mostly outlines and shadows, darting in and out of time. At Bill’s studio, Schloss, who’d escaped Nazi Germany studying languages abroad as a teenager, first beheld the takeover of former industrial spaces that transformed real estate as well as art. So powerful was the romance of New York lofts, surpassing the Parisian garrets before them, that prefabricated luxury versions are now an industry standard. They were “stages for work and for a whole new free way of living,” Schloss writes, describing her crowd’s appropriation of cable spools for coffee tables as if they were The Borrowers, a perpetual ascension of creaky stairs, parlor games absent an actual parlor and meals taken at the Automat.

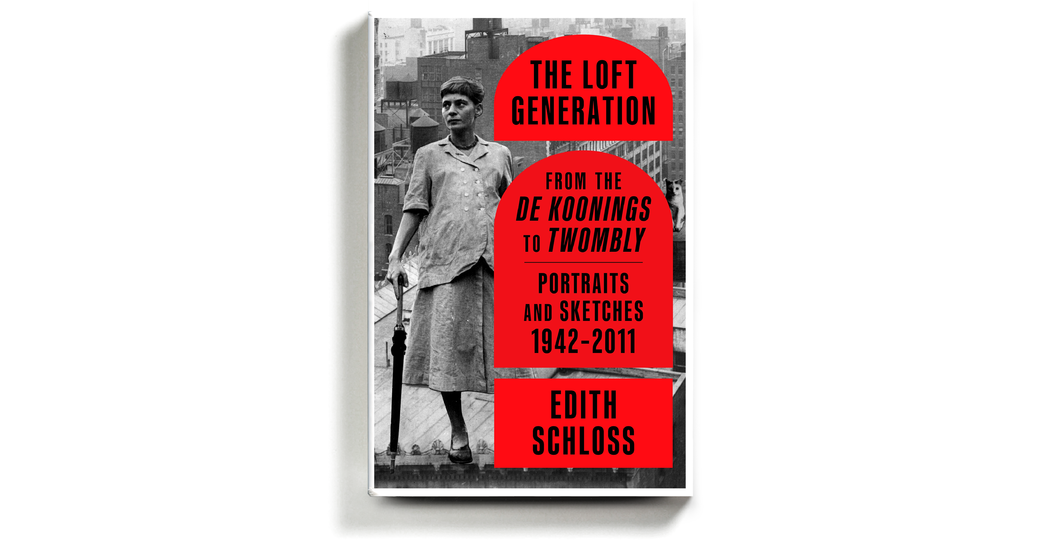

All five senses are shaken awake by “The Loft Generation,” which might as well be subtitled A Study of Synesthesia, punctuated by “cream-colored screams,” a hotly debated phrase the poet Frank O’Hara used to describe Cy Twombly’s canvases in ARTnews. Schloss got a reviewing gig there — she compares the work to embroidery or knitting — to smoothe Jacob’s admittance to a nursery school “only for the children of working mothers”; painting apparently didn’t qualify. There is sight, of course, with color insets of Schloss’s bright and optimistic daubings alongside work by her more dour-seeming contemporaries. There is sound, in her recounting of the unholy clamor of the Chelsea neighborhood where she and Burckhardt shacked up: the rattling of iron window shutters, mating cats, the fire and burglar alarms and “the intermittent swish of cars down Sixth Avenue, like long sighs.” (Next time you misplace the AirPods Pro, think of John Cage teaching Schloss to appreciate ambient noise as part of life’s symphony.)