SEOUL — Song Chun-son, a duck farm worker, endured two and a half years in a North Korean labor camp and was later coerced to work for its secret police, the Ministry of State Security. Then she defected to South Korea in 2018, trying to start a new life here. She studied to become a caretaker for nursing home patients while working part time as a waitress.

That was until South Korean counterintelligence officers caught up with the details of her past in North Korea.

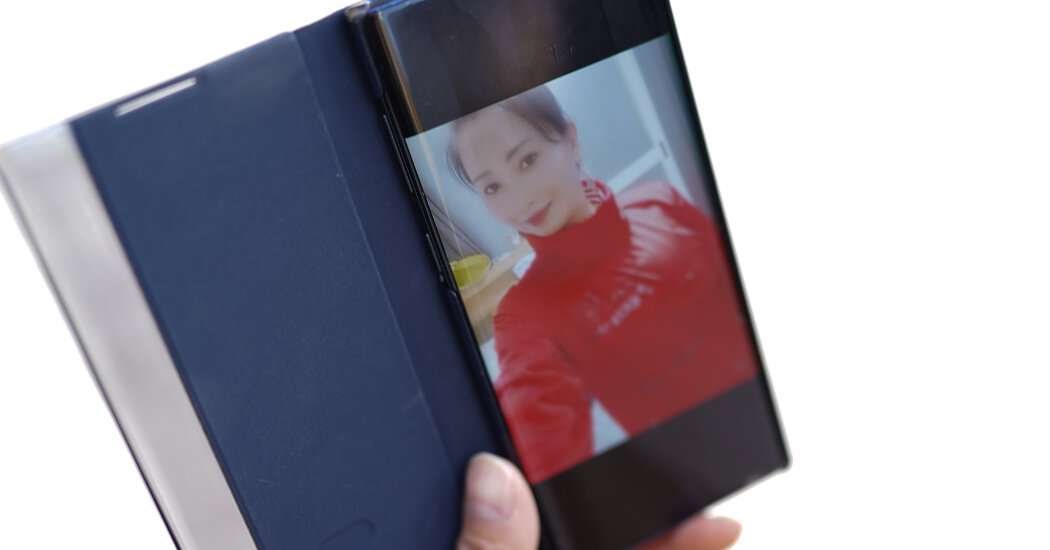

In May, they arrested Ms. Song, 44, on charges of helping the Ministry of State Security lure or blackmail North Korean defectors living in South Korea into returning to the North. Her case has since provided rare glimpses into the clandestine battle the rival Koreas have waged over North Korean defectors living in the South.

Under its leader, Kim Jong-un, North Korea has plotted to lure North Korean defectors in the South back to their former homeland using whatever means it could, including recruiting people like Ms. Song. But the South’s counterespionage authorities are equally determined to thwart the North’s operation, carefully screening newly arriving defectors from the North, like Ms. Song, to catch anyone linked to its efforts.

On Tuesday, a court in Suwon, south of Seoul, sentenced Ms. Song to three years in prison. Instead of enjoying her new freedom, she finds herself sitting in a prison cell in the South, having become a pawn in the cloak-and-dagger war between her old and new home countries.

“When I came to South Korea, I confessed to what I did in the North to make a fresh start in the South,” Ms. Song said in an August letter she sent from jail to her sister, also a North Korean defector in the South. “I was coerced to do what I did — but they say that doesn’t erase the crime.”

More than 33,800 North Koreans have defected to South Korea since the 1990s. But since Mr. Kim took power a decade ago, at least 28 of them have mysteriously resurfaced in North Korea. How and why they went back to the totalitarian state they had risked their lives to flee has been one of the great mysteries in inter-Korean relations. (South Korean officials fear that some of the hundreds of defectors who have disappeared in recent years may have also ended up in the North.)

North Korea has used the returnees for propaganda, arranging news conferences where they described how lucky they were to escape the “living hell” they found in the South to return to the “bosom of the fatherland.”

Ms. Song’s arrest showed that South Korea’s counterintelligence officials were not sitting idle. Between 2009 and 2019, they arrested at least 14 North Koreans who entered South Korea as defectors, accusing them of arriving here on spy missions that included plots to bring fellow defectors back to the North, according to government data submitted to the National Assembly.

Ms. Song told the court about how she ended up going to South Korea. A native of Onsong, a North Korean town near the Chinese border, she had been working as a broker, helping North Korean defectors in the South transfer cash remittances to their relatives in the North when the Ministry of State Security recruited her in 2016.

Confronting her about her illegal work as a cash broker, the ministry gave her a stark choice: serve time in a prison camp or cooperate with its agents to lure North Korean refugees in South Korea back to the North. For Ms. Song, who had already been in a labor camp from 2007 to 2009 for the crime of illegally entering China for food in the wake of a famine in the North, the choice was obvious.

“She had to cooperate to stay alive, she had no other choice,” said her sister, Chun-nyo, who defected to South Korea in 2019.

In the court hearing on Tuesday that sent Ms. Song to prison, the presiding judge, Kim Mi-kyong, dismissed her appeal, saying that she had helped the North Korean secret police for personal gain as well.

During her trial, Ms. Song admitted providing a secret police agent named Yon Chol-nam with the telephone number of a North Korean defector in South Korea she had known while working as a broker. She also admitted calling the defector to ask him help Mr. Yon, lying that the agent was her husband and that he worked for North Korean families trying to reach their defector relatives in the South.

With the defector’s help, Mr. Yon located three North Korean defectors in the South, prosecutors said. He tried to persuade them to return to the North by putting their North Korean relatives on the phone with them. One of the defectors, Kang Chol-woo, and his girlfriend, also a North Korean defector in the South, returned to the North through China in 2016 and later appeared on North Korean TV.

In August 2016, the ministry sent Ms. Song to China to spy on North Korean migrants there and on Christian missionaries who helped them flee the North. It gave her a code name: “Chrysanthemum.” But after two years, she fled to South Korea, where she told her debriefers what she did for the North’s Ministry of State Security.

“She thought she was cleared when she was released from the debriefing center to live a new life in the South,” said her lawyer, Park Heon-hong.

However, Ms. Song had unwittingly stepped into the fierce spy war over North Korean defectors.

Under Kim Jong-un, North Korea has tightened its control over the border with China, the main escape route for defectors. And it has intensified its crackdown on the South Korean TV dramas and music smuggled from China through which North Korean defectors learned of life in the South.

Partly as a result of these crackdowns, the number of North Korean refugees arriving in the South dropped to 1,047 in 2019 from 2,914 in 2009. The number plummeted to 229 last year, as the pandemic led to further border restrictions.

North Korea has called the defectors “traitors” and “human scum.” But its online propaganda channels have also interviewed family members who tearfully appealed to defectors, telling them that Mr. Kim promised to forgive their crimes if they returned home.

South Korea has put its guard up, catching North Korean agents disguised as defectors who entered South Korea on clandestine missions to assassinate fellow defectors or lure them back to the North.

But South Korean counterintelligence officials also have a history of fabricating evidence in their overzealous hunt for North Korean spies. In 2016, South Korea announced the arrival of 12 young North Korean waitresses and their male manager, billing their defections as a major coup against Pyongyang. The manager later said that the South’s National Intelligence Service plotted with him to bring the women here against their will.

“Ms. Song thought she escaped from the grips of the Ministry of State Security when she defected to the South,” said Jung Gwang-il, a North Korean defector who leads No Chain, a civic group working for North Korean human rights. “But waiting for her in the South were counterintelligence officers eager to make what little score they could against the North.”