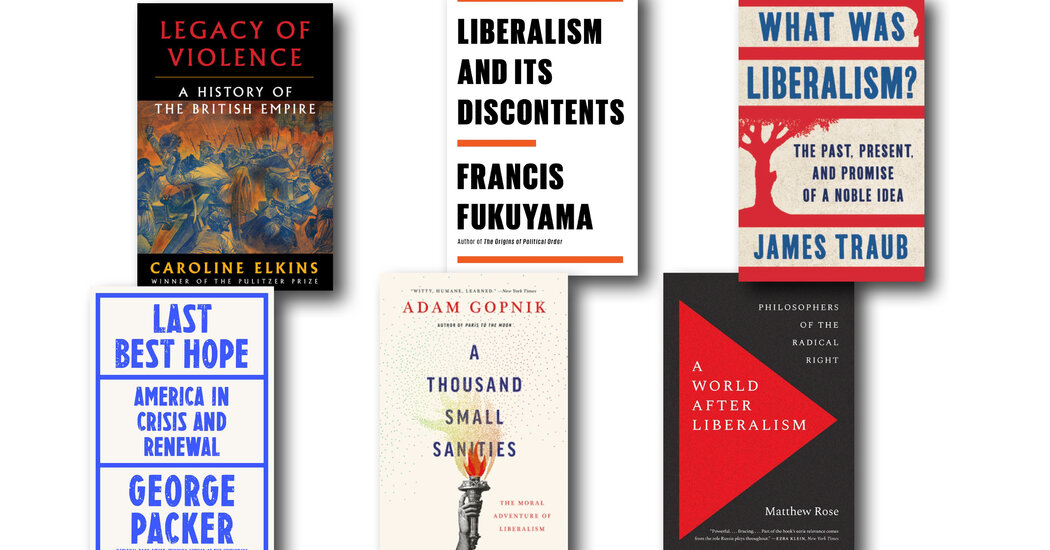

Liberalism, then, has been spectacularly hypocritical — though Fukuyama, for one, is unimpressed with the charge, arguing that this leftist critique “fails to show how the doctrine is wrong in its essence.” The historian Caroline Elkins might beg to disagree. In “Legacy of Violence,” her recent book about the British Empire, she argues that “ideological elasticity” was in fact what made liberal imperialism so resilient. She shows how Britain’s vast apparatus of laws was used to legitimize the violence of its “civilizing mission.” What Fukuyama repeatedly refers to as liberalism’s “essence” has also, Elkins suggests, amounted to a paradox: emancipation and oppression, all rolled in one.

But such tensions are less interesting to liberalism’s conservative critics, who think that it’s rotten all the way down. As Matthew Rose puts it in “A World After Liberalism,” the radical right has long deemed it “evil in principle because it destroys the foundations of social order.” The 20th-century extremist thinkers he discusses in his book — among them a “fascist savant” and a “right-wing Marxist” — derided Christianity, too, for an egalitarianism and compassion that they just couldn’t abide. Still, their critiques have found echoes in contemporary arguments by right-wing Christians like Sohrab Ahmari and Patrick Deneen, who blame liberalism for making people comfort-seeking and spiritually lazy.

Liberal decadence doesn’t amount just to temptation but to tyranny — or so you might believe when reading liberalism’s most vociferous detractors on the right, whose sweeping denunciations can make it sound as if there’s a liberal regime coercing women into pursuing careers and forcing them to get abortions. It’s notable how little liberalism’s book-length defenders have to say about sexual and reproductive rights, while conservative critics have long been fixated on them. Gopnik did warn that if the anti-abortion movement truly meant business, it would have to create some sort of invasive “pregnancy police force.” He didn’t foresee that Texas would soon figure out a way to do something even more extreme by putting that power in the hands of civilians — a vigilante-enforced ban on abortion, on the cheap.

There’s an old essay by the feminist cultural critic Ellen Willis in which she said that “sophisticated liberals” seemed so “emotionally intimidated” by the anti-abortion movement that they didn’t quite know how to talk about it: “Nearly everyone I know supports legal abortion in principle, but hardly anyone takes the issue seriously.” Willis wrote this in 1980, calling the anti-abortion movement “the most dangerous political force in the country,” one that posed a threat not only to sexual freedom and privacy but also to physical autonomy and “civil liberties in general.”

Willis pointed to liberalism’s weaknesses while also identifying the room it had opened up for liberation. She had gotten her start as a rock critic, a woman in a male-dominated field, ever aware of the possibilities and limitations afforded by the mainstream culture. The late philosopher Charles Mills was similarly attuned to such discrepancies. In books like “The Racial Contract” and “Black Rights/White Wrongs,” he offered scathing critiques of a “racialized liberalism” that kept trying to pretend it was colorblind; Mills argued that liberalism’s exclusions were historically so vast that they weren’t mere anomalies but clearly fundamental to it.

Still, as he told The Nation in early 2021, “liberalism is attractive on both principled and strategic grounds.” Mills envisioned a liberalism that was tougher and more radical, yet imbued with some necessary humility — a sense of how contingent it was. It was precisely the experience of subordination and exclusion that made him alert to what many liberals didn’t want to see. He ended an essay for Artforum in 2018 with a warning: “As the anti-Enlightenment bears down on us, threatening a new Dark Age, just remember: We told you so (and long ago, too).”