PARIS — Emmanuel Macron won a second term as president of France, triumphing on Sunday over Marine Le Pen, his far-right challenger, after a campaign where his promise of stability prevailed over the temptation of an extremist lurch.

Projections at the close of voting, which are generally reliable, showed Mr. Macron, a centrist, gaining 58.5 percent of the vote to Ms. Le Pen’s 41.5 percent. His victory was much narrower than in 2017, when the margin was 66.1 percent to 33.9 percent for Ms. Le Pen, but wider than appeared likely two weeks ago.

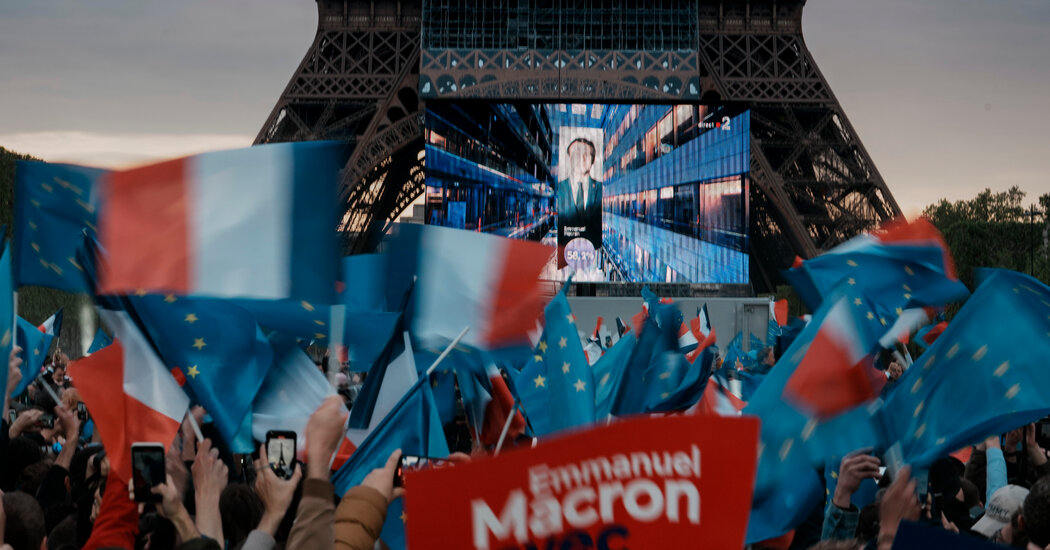

Speaking to a crowd massed on the Champ de Mars in front of a twinkling Eiffel Tower, a solemn Mr. Macron said his was a victory for “a more independent France and a stronger Europe.” At the same time he acknowledged “the anger that has been expressed” during a bitter campaign and that he had duty to “respond effectively.”

Ms. Le Pen conceded defeat in her third attempt to become president, but bitterly criticized the “brutal and violent methods” of Mr. Macron. She vowed to fight on to secure a large number of representatives in legislative elections in June, declaring that “French people have this evening shown their desire for a strong counter power to Emmanuel Macron.”

At a critical moment in Europe, with fighting raging in Ukraine after the Russian invasion, France rejected a candidate hostile to NATO, to the European Union, to the United States, and to its fundamental values that hold that no French citizens should be discriminated against because they are Muslim.

Jean-Yves Le Drian, the defense minister, said the result reflected “the mobilization of French people for the maintenance of their values and against a narrow vision of France.”

The French do not generally love their presidents, and none had succeeded in being re-elected since 2002. Mr. Macron’s unusual achievement in securing five more years in power reflects his effective stewardship over the Covid-19 crisis, his rekindling of the economy, and his political agility in occupying the entire center of the political spectrum.

Ms. Le Pen, softening her image if not her anti-immigrant nationalist program, rode a wave of alienation and disenchantment to bring the extreme right closer to power than at any time since 1944. Her National Rally party has joined the mainstream, even if at the last minute many French people seem to have voted for Mr. Macron to ensure that France not succumb to the xenophobic vitriol of the darker passages of its history.

Ms. Le Pen is a longtime sympathizer with President Vladimir V. Putin of Russia, whom she visited at the Kremlin during her last campaign in 2017. She would almost certainly have pursued policies that weakened the united allied front to save Ukraine from Russia’s assault, offered Mr. Putin a breach to exploit in Europe, and undermined the European Union, whose engine has always been a joint Franco-German commitment to it.

If Brexit was a blow to unity, a French nationalist quasi-exit, as set out in Ms. Le Pen’s proposals, would have left the European Union on life support. That, in turn, would have crippled an essential guarantor of peace on the continent in a volatile moment.

Olaf Scholz, the German Chancellor, declared that Mr. Macron’s win was “a vote of confidence in Europe.” Boris Johnson, the British Prime Minister, congratulated the French leader and called France “one of our closest and most important allies.”

Mr. Scholz and two other European leaders had taken the unusual step this week of making clear the importance of a vote against Ms. Le Pen in an opinion article in the daily newspaper Le Monde. The letter was a reflection of the anxiety in European capitals and Washington that preceded the vote.

“It is the choice between a democratic candidate, who believes that France is stronger in a powerful and autonomous European Union, and a far-right candidate, who openly sides with those who attack our freedom and our democracy — fundamental values that come directly from the French Enlightenment,” they wrote.