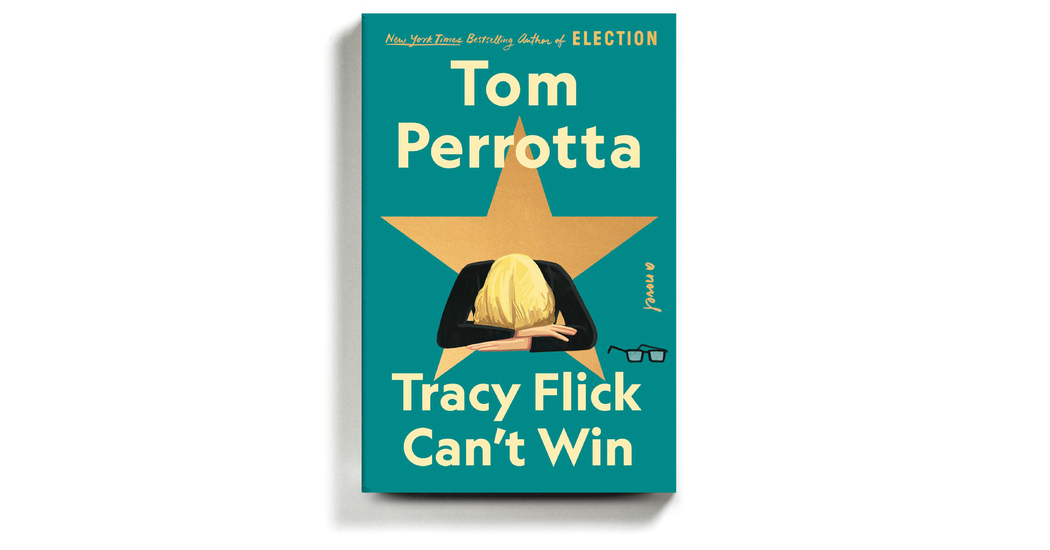

TRACY FLICK CAN’T WIN

By Tom Perrotta

259 pages. Scribner. $27.

Tom Perrotta’s characters commit routine moral crimes: They betray spouses, treat friends shabbily, send inappropriate text messages, disrespect their parents, scheme to unseat rivals. These people aren’t serial killers or Marvel villains; their sins are prosaic. Twenty years ago, Us Weekly magazine launched a feature called “Stars — They’re Just Like Us!” which depicted celebrities buying dog kibble or waiting for luggage at the airport. You can’t read a novel like “The Leftovers” or “Mrs. Fletcher” without a similar thought flashing across your mind: “Tom Perrotta Characters — They’re Just Like Us!”

Perrotta’s new novel has a title of a now-familiar kind: the main character’s full name, plus a statement that ironically summarizes the book’s contents. Think of “Eleanor Oliphant Is Completely Fine” or “Florence Adler Swims Forever” or “Lorna Mott Comes Home.” And now “Tracy Flick Can’t Win,” which is better than those books and even more piercing than its predecessor, “Election” (1998), the novel that introduced us to the shatterproof Tracy Flick.

Tracy was immortalized by Reese Witherspoon in Alexander Payne’s 1999 film adaptation of the novel. Witherspoon, who has incidentally been featured in “Stars — They’re Just Like Us!” feeding money into a parking meter, gave one of the best comic performances of the decade. Never has a nostril been flared with greater virtuosity. But the movie departed significantly from the source material. Payne switched the setting from New Jersey to Nebraska, rewrote the ending and made Tracy more of a demon.

The new book starts in the thick of #MeToo. Powerful men are being revealed as sleazeballs, and Tracy, now in her 40s with a daughter, wonders whether she has misjudged her own past. In “Election,” she had an “affair” with a high school teacher. Until recently, she has refused to classify herself as a victim. But as stories of high-achieving young women exploited by mentors and bosses pile up in the news, her own narrative starts to feel, in her words, “a little shaky.”

The teacher, Mr. Dexter, is now dead of prostate cancer, and Tracy is assistant principal at a suburban high school. You wouldn’t think that she would end up as a deputy anything (rather than the sheriff), but there have been mitigating factors. When her mother became ill, she dropped out of law school and moved back home. Instead of pursuing justice as a lawyer or saving lives as a doctor or doing nothing as a senator, she toils in a cramped office handling locker assignments and complaints about cafeteria food.

As in “Election,” this novel revolves around a competition. Tracy’s boss is about to retire, and Tracy must beat out other candidates to assume the job of principal. As in the student election of the previous book, Tracy believes that she deserves the position. And by every quantifiable measure, she does. But when a superintendent asks her why she thinks she’s ready for the job, she makes the error of telling the truth: “I’ve paid my dues.”

Advancement in most white-collar jobs is less about actual competence than about convincing people in power that you’re competent, even if you’re not. That, and possessing a quality related to likability but not identical to it — the quality of being a person whom other people want to see succeed. Tracy passes the competency test with flying colors; but nobody wants her to move up the ladder.

Why? That was the question that propelled “Election.” Tracy was hardly a threat to the high school food chain. She was lonely and insecure, plagued by stomach issues and insomnia. She burned with jealousy watching a pair of students kiss “like they were getting nourishment from each other’s tongues.” She baked cupcakes for people who wouldn’t bother to sign her yearbook. In other words: an underdog cursed, for some reason, to be construed as an infuriating alpha who needed to be put down.

In his sequel, Perrotta elaborates on the case of Tracy’s mistaken identity. Do people (mostly men, but some women) hate her because of … misogyny? Or is it because they can’t stop themselves from punishing a person who insists, absurdly, on believing that life should be fair? Or is it because Tracy, for all her political ambitions, still fails to grasp the most important political skill of all, which is the gift of making other people feel good about themselves?

In middle age, Tracy’s optimism (or naïveté) is unchanged. There are two ways to look at this. Maybe it’s a credit to her integrity that she hasn’t been squashed into submission. Maybe it’s preposterous that she refuses, after all this time, to play by the rules of the game. Even if the game is rigged. Even if she shouldn’t have to play it.

Perrotta sidles up to this drama from many directions. Each chapter in “Election” was a first-person account from one of six characters. The new book is split between chapters like that and sections written in a close third person. The cast includes a former athlete, a rich tech guy, a long-suffering admin, two students and the school principal. All are exquisitely drawn.

There’s Jack Weede, Tracy’s boss, who reminisces about the golden days when students smoked Marlboros in the bathrooms, beat up gay kids and verbally rated girls on a scale of one to 10. His take on #MeToo: “It’s like the French Revolution. They had a just cause, but they got a little overzealous with the guillotine.”

There’s Kyle Dorfman, the tech guy, who made his fortune in Silicon Valley with a dumb app and then returned home to throw his weight around as head of the school board. “When I call myself a visionary, I don’t mean that in a grandiose way,” he says, before outlining a quixotic desire to build a “Hall of Fame” showcasing the school’s mostly unimpressive alumni. Eight months in, he’s already frustrated by the board’s “resistance to change and creative disruption.” Few novelists are better than Perrotta at conveying the full spectrum of human delusion.

Which brings us back to Tracy. Will our heroine, having been pummeled with 20 years’ worth of lemons, continue to make lemonade that nobody wants to drink? Or will she go berserk and blow up the system? Perrotta veers off in an ingenious third direction. Life suddenly, and startlingly, comes to match the intensity of Tracy’s vision of it.